Dispatches from the Vault 23.1

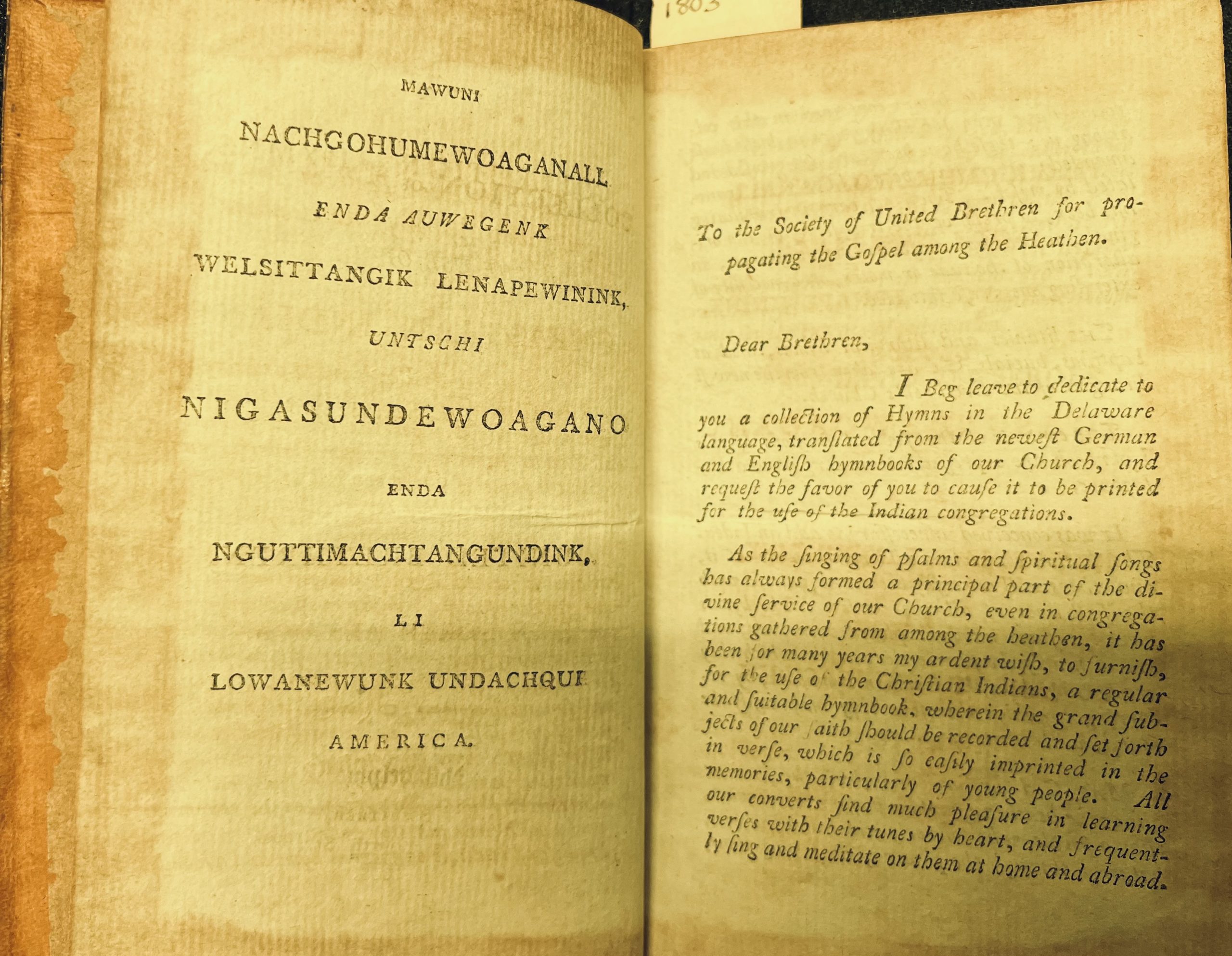

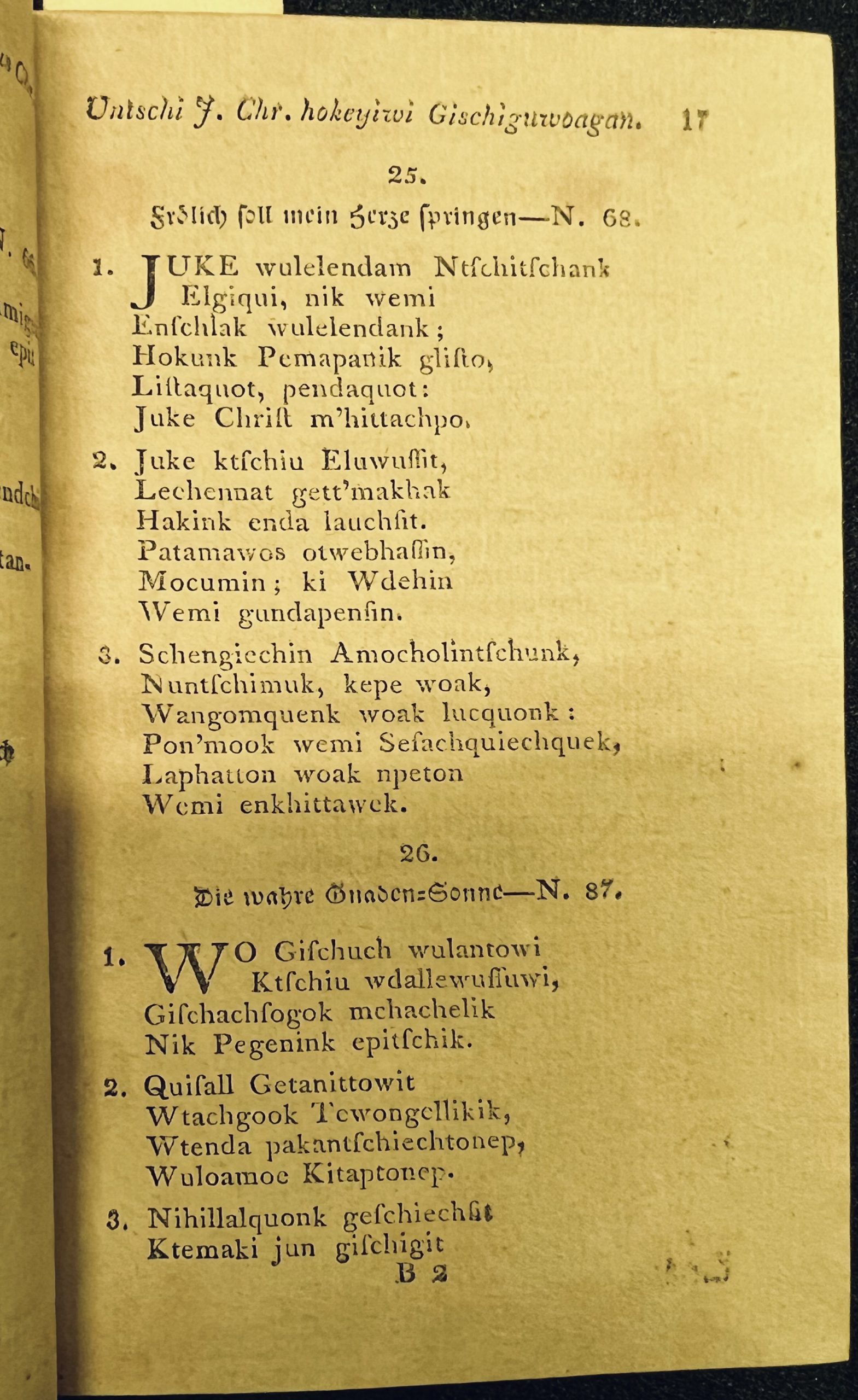

A Collection of Hymns for the use of the Christian Indians of the Missions of the United Brethren, in North America

David Zeisberger (1721–1808) was born in Suchdol nad Odrou (German: Zauchtenthal) in the present-day Czech Republic.

With the founding and expansion of Herrnhut in the early 1720s, many residents of Suchdol sought refuge in the new community, including Zeisberger’s parents, David and Rosina, who soon arrived with their children. In the following years, the church turned towards missionary work, sending members of the congregation out into the world. In 1736, David and Rosina joined this movement and traveled to Georgia, becoming part of the first foray of Moravians into the American colonies. Two years later, Zeisberger reunited with his parents, having spent the intervening years in the Netherlands and England. After the outbreak of the War of Jenkins’ Ear (a conflict between Great Britain and Spain that was partly instigated by Captain Robert Jenkins brandishing a severed ear in the House of Commons, which he claimed had been amputated by Spanish coast guards who boarded his ship), the family migrated to Pennsylvania, where they helped to build Bethlehem.

In 1745, Zeisberger began the work that would become his life’s mission. Traveling to Onondaga, he began preaching to Indigenous communities. In his travels, he also gained some familiarity with the culture and languages of the people that he met, which made him an important translator and mediator between these communities and European settlers. Eventually, he met the Lenape people, who were the original inhabitants of the Delaware Valley in what now comprises areas of Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York. Europeans began to refer to the Lenape as “Delaware Indians” based on where they lived (the Delaware River had derived its European name from Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr, the first governor of the Colony of Virginia). As the Lenape were forced to move westward into Ohio and Canada, the Moravian missionaries traveled with them, forming missionary communities in these new regions. It was here that Zeisberger’s work with the Lenape primarily took place.

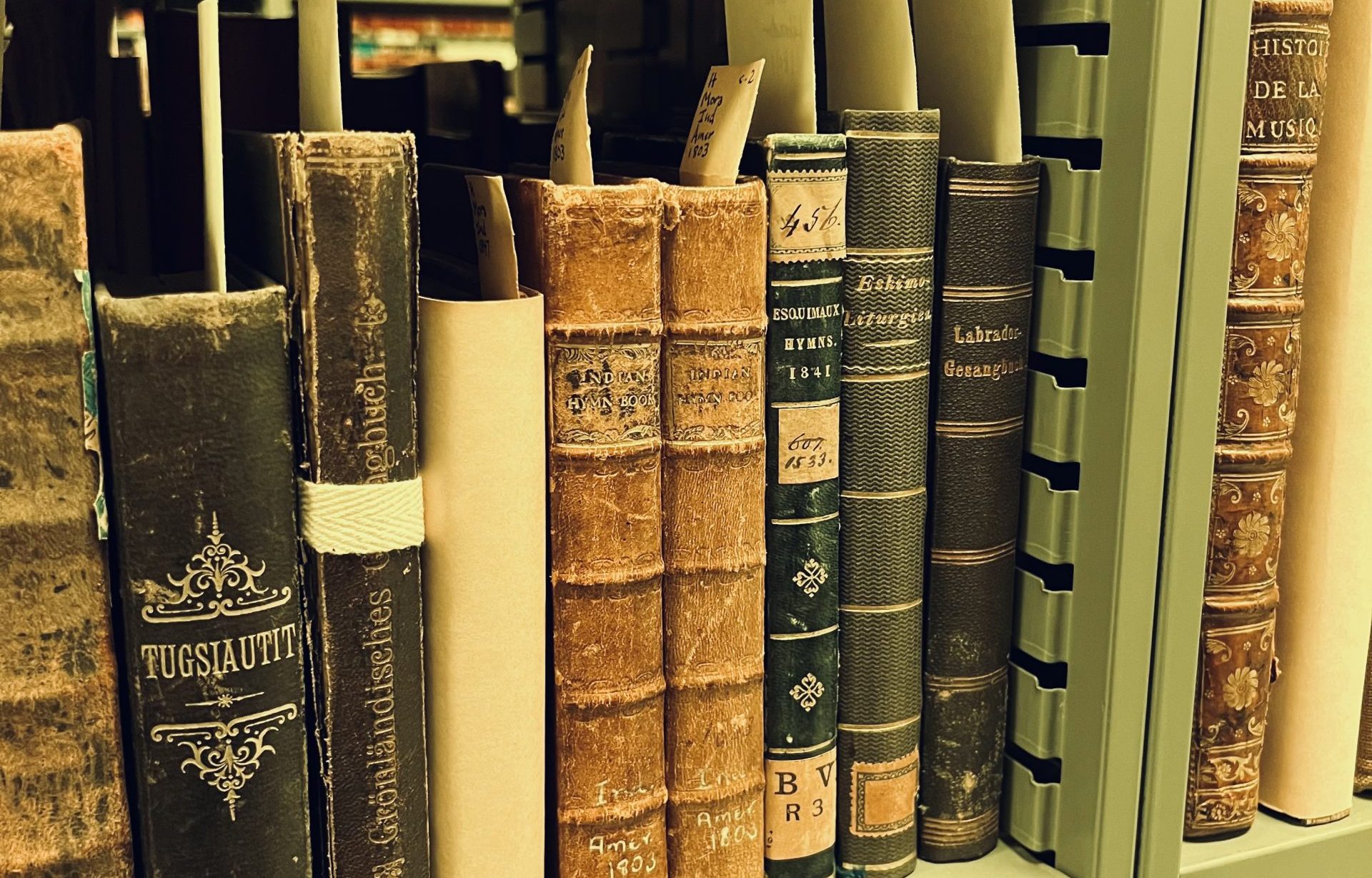

hymnals in the MMF archival collection (W-S)

The hymnal by Zeisberger was not the first one translated into the language of the Lenape people. In 1763, Bernhard Adam Grube published Dellawärishes Gesang-Büchlein. This collection contained favorite hymns of the converted Lenape. In 1772, the task of revising the hymnal was given to Zeisberger, who worked on the project from 1772 to 1803 with the assistance of fellow missionaries and a group of Indigenous people. Music, which always served as a vital tool for the Moravian missionaries, emerged as a significant bridge between the two cultures, both of which placed a high value on the act of music making. As elsewhere, it also functioned as a means of transmitting theology, which was even more important when surmounting linguistic and cultural barriers.

The legacy of the Moravians and Zeisberger’s work with the Lenape people is complicated. From the beginning, there was tribal support for this missionary work, which resulted in prominent figures within the tribe converting to Christianity.

There was also an effort on the part of the missionaries to preserve some Lenape cultural practices. Zeisberger, who demonstrated an interest in preserving the languages of Indigenous communities, worked to create dictionaries and translations of hymns, the Bible, and other types of educational materials. This is where the hymnal found in our collection derives. Looking back on the impact of these efforts, the Lenape have expressed a certain ambivalence towards the Moravian missionaries. On the one hand, there was a lot of good work done towards the preservation of the language and the creation of invaluable resources towards that goal, many of which are still used today. On the other hand, the Lenape have questioned whether the practice of teaching reading and writing skills only to those Lenape who had converted, rather than to all the Lenape people, suppressed the flourishing of a vibrant literary culture and tradition. In spreading their message, the Moravians may also have damaged the preservation of some cultural practices owing to the strict rules and codes of conduct that were customary among missionaries and mission communities at the time. While some practices remained, there were many others that were prohibited. As a case in point, Zeisberger recorded a set of statutes that were agreed upon at Lagundo Utenunk and Welhik-Thuppeek in August 1772. The list included the banning of several expressions of Indigenous culture, such as attending “heathen feasts and dances held at other places,” using “objects of heathen superstition in hunting or in curing diseases,” and forbidding the use of paint or hanging “wampum, silver or anything on himself.” These codes of behavior had the effect of suppressing certain acts of cultural expression, including dance and dress, which may have contributed to their decline over the years.

This hymnal stands as a powerful reminder of this complex legacy.

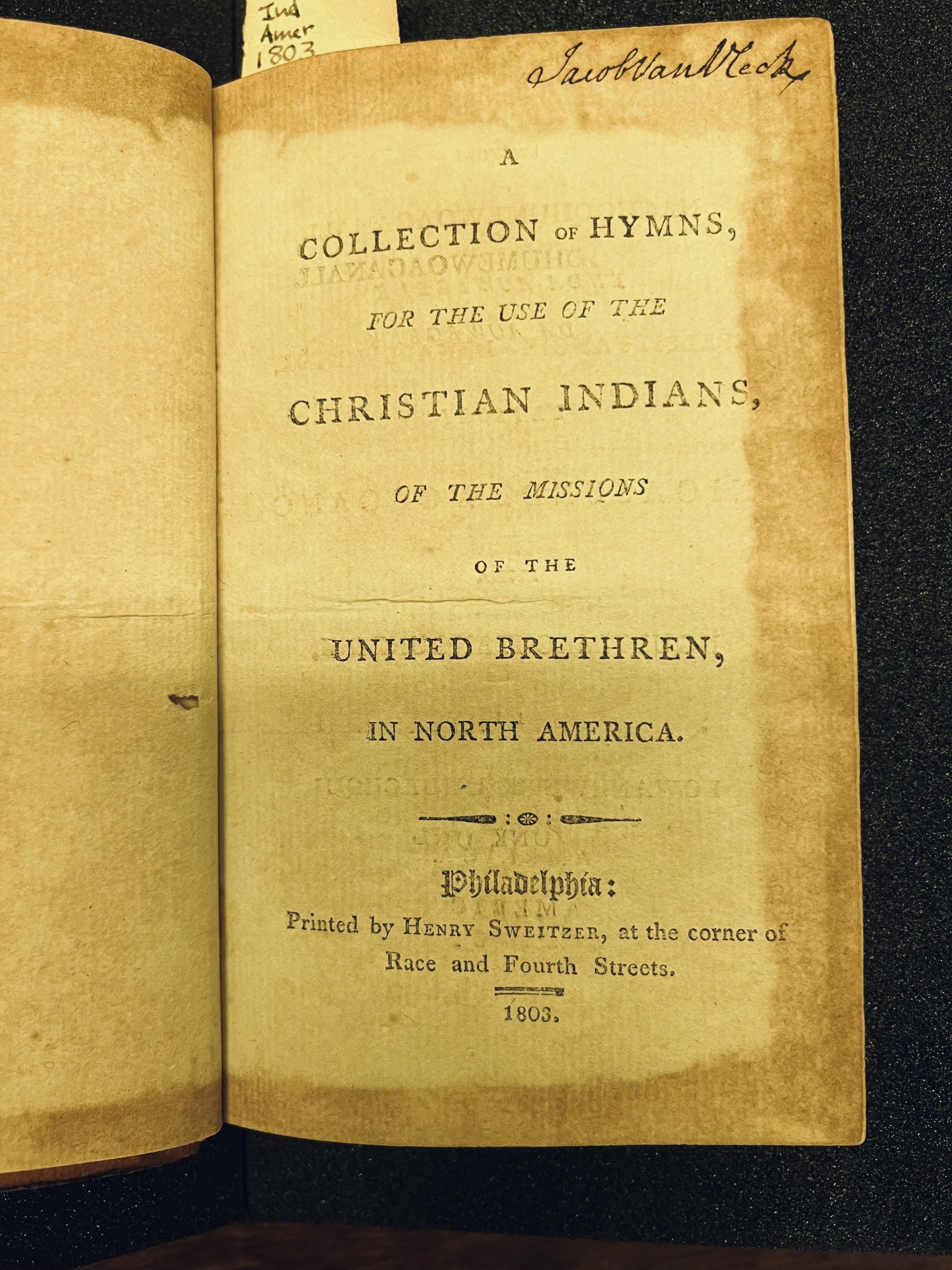

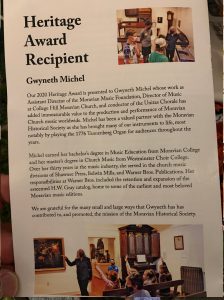

Note about the owner: One of the copies found in the vault is inscribed with the name Jacob Van Vleck (1751–1831).

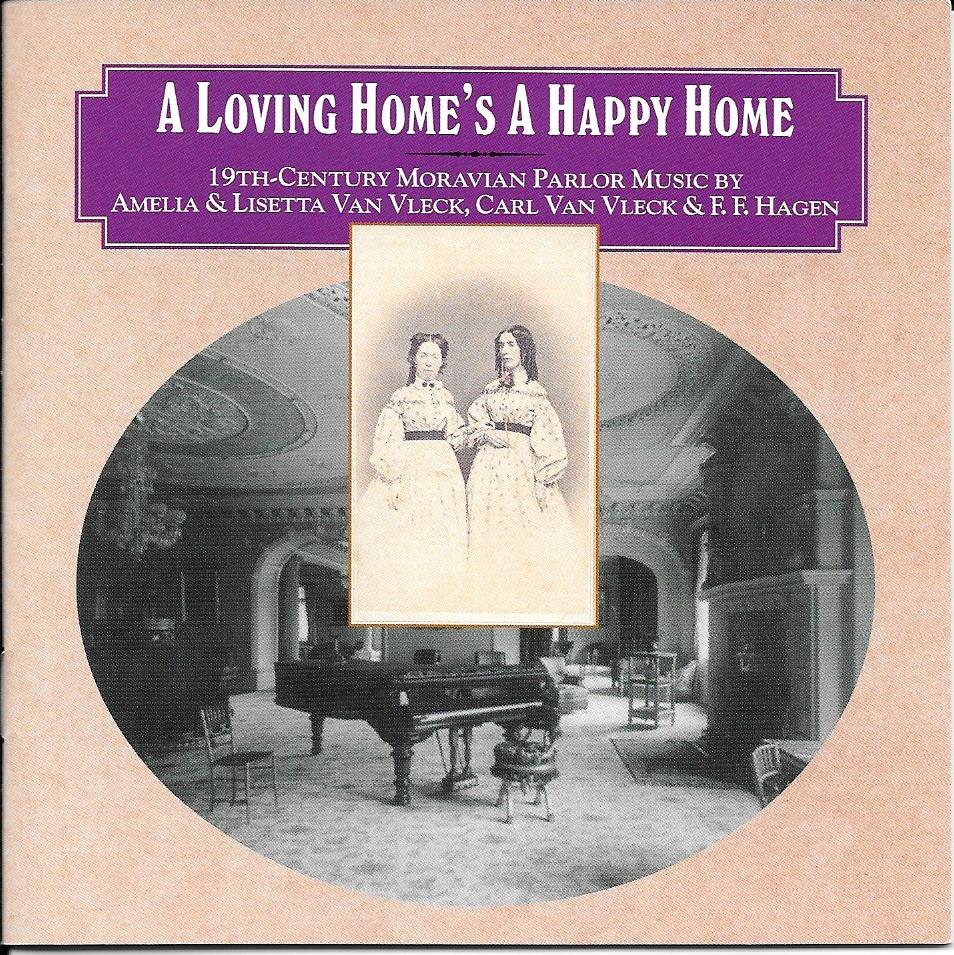

Some of his music, and that of his daughters, is included on the MMF CD, A Loving Home’s A Happy Home, available here and currently on sale (double CD – Only $14).

A prominent figure in the Moravian Church, Jacob Van Vleck has the distinction of being the first American-born bishop of the Church. In addition to the numerous positions he held, he was also an accomplished composer and musician, who reportedly played the organ during Washington’s visit to Bethlehem in 1782. Beginning in 1812, he served as the pastor of Salem congregation, where he remained for a decade before returning to Bethlehem.

Leave a Reply