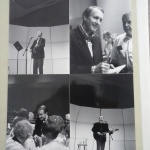

George Hamilton IV performed at the 1972 and 1990 Moravian Music Festivals

Winston-Salem Journal

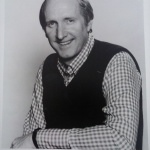

George Hamilton IV, a Winston-Salem native who became a country music legend known for his clean-cut look and easy going manner, has died.

Hamilton, 77, died Wednesday at a hospital in Nashville, The Nashville Tennessean reported.

Hamilton had suffered a heart attack over the weekend.

His career spanned more than 60 years during which he evolved from being a teen star to folk country and traditional gospel music. As a youngster, he attended Fries Memorial Moravian Church and would go on to be an advocate for the Moravian Church’s music and culture.

Hamilton was born in Winston-Salem on July 19, 1937. He told the Winston-Salem Journal in 1989 that both his grandfathers had been railroad men in the community by the old Union Station near what is now Winston-Salem State University. He grew up in a small brick home on Queen Street, which now overlooks Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. ‘

City start

Although he would become a country star, his upbringing was more city than country. His father, George Hamilton III, was a high-ranking executive at Goody’s Manufacturing Corp. But the younger Hamilton nonetheless found his calling in country music, moved by the songs of Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams Sr., Red Foley, Hank Snow and Eddy Arnold.

Hamilton graduated from Reynolds High School, where he performed in a trio called the Serenaders. It was also at Reynolds that he met Adelaide “Tinky” Peyton, who he would marry in 1958. They have three adult children.

After high school, he left Winston-Salem to attend UNC Chapel Hill.

It was at Chapel Hill, during his freshman year, that he would meet two of the biggest influences of his musical career. One was Orville Campbell, the former publisher of The Chapel Hill Newspaper and the founder of Colonial Records who had gained fame for recording Andy Griffith’s comedy classic “What It Was, Was Football.” The other was a songwriter from Durham named John D. Loudermilk.

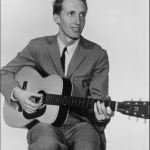

Their musical collaboration led to Hamilton’s first hit, “A Rose and a Baby Ruth,” in 1956. The song, a simply arranged apologetic teen love anthem, reached the national Top 10.

In a Journal interview in 2010, Hamilton recalled playing the grandstand at the Dixie Classic Fair shortly after the song became a hit. He said that playing before a hometown crowd held special meaning for him.

“That was quite a thrill,” he said.

Early rock star

The record made Hamilton a pop star and allowed him to tour with some of the early stars of rock ’n’ roll, including Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and the Everly Brothers. He was inducted into the Teen-Age Heart Throb Club along with Paul Anka, Frankie Avalon and Bobby Darin.

But Hamilton yearned to make music more like his country music heroes. So he moved to Washington, D.C., where he enrolled in American University. He also regularly performed on Jimmy Dean’s “Town and Country Jamboree” and a TV talent show hosted by Arthur Godfrey.

Hamilton began what would be a long and close relationship with the Grand Ole Opry in 1960. He moved to Nashville, where he met guitarist and producer Chet Atkins.

Atkins signed Hamilton to a record deal and produced his first Top 10 country hits, “Before This Day Ends” and “Three Steps to the Phone.”

In 1963, he had his only No. 1 country song, “Abilene,” which Loudermilk co-wrote with Bob Gibson and Lester Brown. The song also reached No. 15 on the pop charts.

He had several more songs that would make the country charts, but he never cracked the Top 100 pop charts again.

In the mid ’60s he became interested in folk music through the work of Gordon Lightfoot. In 1968, Hamilton played the Newport Jazz Festival, along with Joan Baez, Janis Joplin and Doc Watson.

‘International Ambassador’

The U.S. hits began to slow down in the late 1970s, but he found new stardom in Canada and Great Britain, where in some ways he was an even bigger star than in the States. He became a regular at the International Festival of Country Music at Wembley Stadium, where he first played in 1969. The BBC gave him a TV series called “George the Fourth: A King in the Country.”

During the Cold War in the early 1970s, he became one of the first American country music stars to play behind the Iron Curtain when he performed in Czechoslovakia.

“It’s kinda nice to try to present our music as a form of American culture that, I think, has some quality to it,” he told the Journal in 1980. “I think it’s modern American folk music, really. I take pleasure in presenting it as a kind of music that evolved out of the folk music of Europe.”

Billboard Magazine would dub him “The International Ambassador of Country Music.”

In the 1980s, he turned more seriously to gospel music, doing tours of churches. He also performed on several Billy Graham Crusades.

In the late 1980s, he was the host of a PBS special “Christmas With Moravians.”

His album “On a Blue Ridge Sunday” earned a Dove Award in 2004.

He continued recording and playing, often performing with his son, “George V.”

But aside from his Opry appearances, the venues would for the most part be smaller. He didn’t mind the intimate venues, seeing them as a way to connect with the audience.

Among his last Winston-Salem appearances was a 2010 concert at the Dixie Classic Fair, performing not at the grandstand but at the clock tower stage. Just as with his first appearance there, the concert gave him a reason to be excited.

“It’s kind of a homecoming, for a kid who grew up in Ardmore and spent a lot of happy times at the Dixie Classic Fair,” he said on the eve of the performance.

Even into his 70s, long after the teen idol days had passed, audiences still came to hear him play his stripped down brand of music and listen to stories about the songs and the simple life.

In an age where stars are known for their diva attitudes, Hamilton remained a grateful and humble star. His wife, Tinky, told the Journal in 1989 that if he had a fault, it may have been that he was too laid back.

“He is really just a good human being,” she said. She acknowledged that in the music business, being easygoing can be a sign of weakness. “But I will say it’s one of the reasons I love him. It’s been that way since the day I met him.”

George was loved on both sides of the Atlantic. I remember a special program on the BBC in London, dedicated just to him. He also entertained many residents and family members at what was once the Moravian Home, and probably later, at Salem Town. I have photos from one of the events. He will be sorely missed!