Dispatches from the Vault

The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion

For this first dispatch, I’m highlighting an item from the Irving Lowens Collection, a significant, yet lesser-known collection housed here at the Archie K. Davis Center in Winston-Salem.

Irving Lowens (1916-1983)

Irving Lowens (1916–1983) was a musicologist, critic, and librarian, who enjoyed a long and illustrious career. He often wore many hats, serving as the chief music critic of the Washington Star from 1960–1978, while also doing a stint as the assistant head of the reference section of the Music Division of the Library of Congress from 1962–1966.

In addition to his work as a critic, he taught at numerous colleges and universities, such as Brooklyn College, CUNY, and the Peabody Conservatory, and founded several scholarly societies, including the Music Critics Association and the American Sonneck Society, now known as the Society for American Music.

One of Lowens’ great passions was the study of American music, which resulted in the publication of his book Music and Musicians in Early America (1964). He recognized that the roots of much of American music lay in the folk hymns and spirituals found in the many hymnals and tune books that were published for amateur singers in the nineteenth century. His love of this music ultimately resulted in a personal collection of over 2000 hymnals and tune books dating from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries that now form the Irving Lowens Collection at the Moravian Music Foundation.

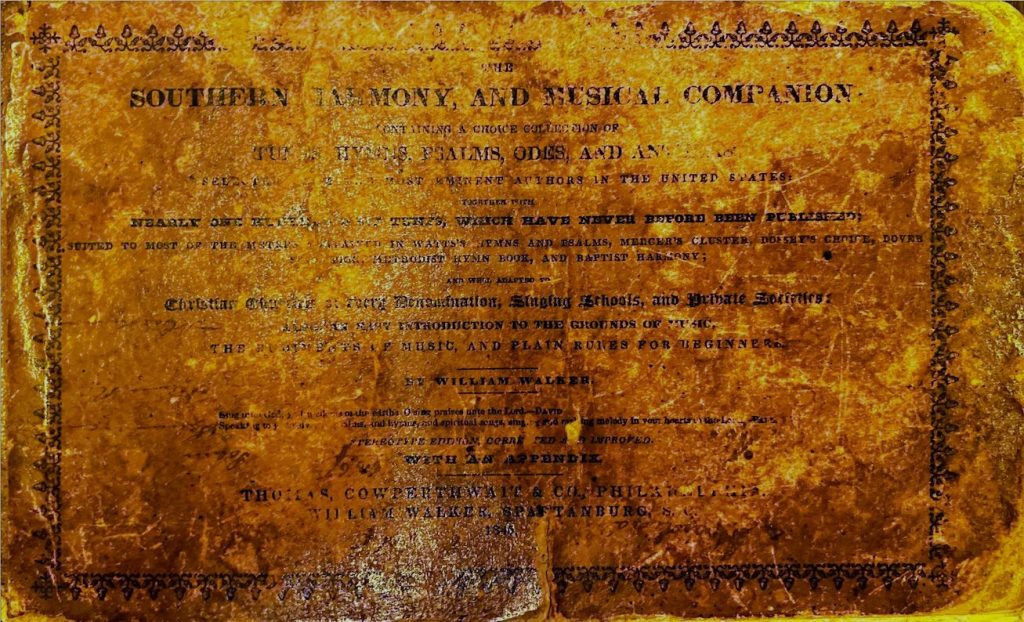

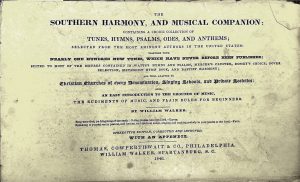

Found in this collection are several editions of The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion, a four-shape tune book that was originally published in 1835. Our oldest edition dates to 1846 and marks one of many reprints and editions over the years. – ex libris: Antoinette Nading (see below) – The Southern Harmony was both the first tune book to become widely popular in the South and the first Southern shape-note book distributed nationally. Its compiler, William Walker, was a Baptist layman from South Carolina, who relied on numerous folk hymns and spirituals, including the newly popular “Amazing Grace,” in assembling his work. His singing schools quickly sprang up throughout the Carolinas, Georgia, and Tennessee. By 1866, he claimed to have sold over 600,000 copies, but that figure is hard to verify. Regardless of the exact numbers, it was one of the most popular tune books of the century and did have a huge influence on later collections, most famously The Sacred Harp. As a disseminator of this music in the South, Southern Harmony invariably inspired many of the performers who would go on to popularize a new genre in the twentieth century originally known as “hillbilly” music before it received its more respectable label of “country” music.

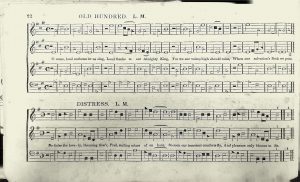

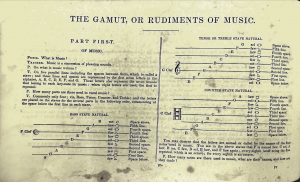

Like many early “shape-note” books, Southern Harmony was known as a “four-shape” tune book. The designation came through its use of a four-syllable (or “fasola”) solmization system, rather than the more common seven-syllable “do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti” made famous by Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music. In this system, each syllable is assigned a shape, for example, the “fa” is a triangle. This helps the singers recognize the different music intervals (the distance between notes), which allows them to sight-sing music without having to recognize pitches on the staff or a key signature, although these elements were still included in the notation. At the beginning of the book, there is a pedagogical section that was designed to teach singers how to use the notation. Publishers were also known to send instructors out to different towns and settlements to teach local communities how to use the books (and sell a few more copies along the way).

The tradition of the American tune book originated with the works of eighteenth century singing-school composers from New England, who introduced the ubiquitous oblong shape of the book, the pedagogical preface, as well as many of the popular tunes that frequently appear. When it comes to the repertoire, a notable aspect of these songs is that the primary melody is often found in the tenor, rather than the soprano (often called the “treble” in these books). This is a tradition that seems to harken back to early polyphonic practices of the medieval period when harmonies were added above and below the melody (this can still be heard in bluegrass music today).

Although primarily religious, these works were often performed outside of worship in gatherings known as “singings.” The typical performance practice is for the group to sit in a square shape, singing toward the middle, with each voice type taking a different side of the square. When there are only three parts, the tenor and treble lines will double each other. In The Southern Harmony, nearly three-quarters of the hymns are for three parts. The responsibility for choosing the song, setting the pitch, and leading the group rotates among the singers.

One of the more popular hymns found in many of these tune books is “Old Hundredth,” which has traditionally been attributed to the French composer Louis Bourgeois (c. 1510–1561) and was found in the Genevan Psalter, a text of metrical settings of the Psalms requested by John Calvin (1509–1564) for his new church. It is a reminder of the diversity of musical works contained in tune books of the time.

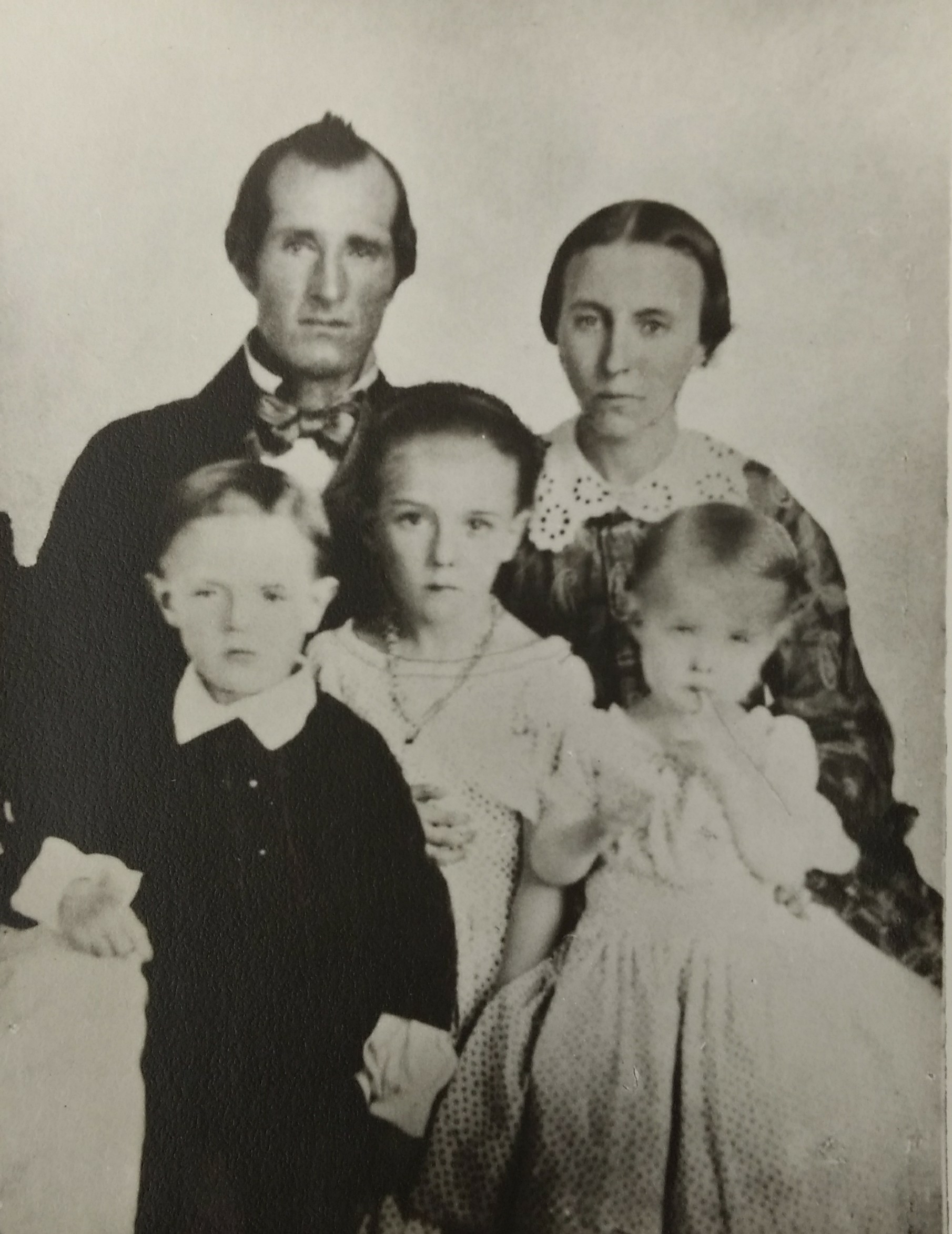

from the library of Antoinette Nading (Reich)

This copy found in the archives has a Moravian connection, having originally been in the possession of Antoinette Nading (1829–1889), who lived in the Salem area and married Augustus Nathaniel Reich (1823–1895) [AKA Gus Rich, magician and entertainer, also drummer in the 26th NC Regiment Band]. She now resides in God’s Acre next to the Foundation that houses her tune book.

Leave a Reply